My predictions for 2011 went up yesterday. Podcast and chat on Thursday.

Somehow I forgot to review Michael Guillen’s Five Equations that Changed the World

, a very strong look at five equations and the scientists who developed them that’s explained with very little math at all. Guillen’s target is the lay reader, a term which, since I haven’t taken a physics class since 1990, would include me.

The five equations aren’t hard to guess – they are, in the order in which Guillen presents them, Newton’s Universal Law of Gravity, Daniel Bernoulli’s Law of Hydrodynamic Pressure, Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction, the Second Law of Thermodynamics (discovered by Rudolf Clausius), and, of course, E = mc

* So, does a scientist discover an equation, develop it, or something else? He doesn’t invent it, certainly; these are, as far as we know, immutable laws of our universe. I thought about using “unearth” to describe this process, but it seems to mundane, especially for Clausius’ and Einstein’s contributions. I’m open to suggestions here.

Newton’s and Einstein’s stories are rather well-known, I think, so I would say the most interesting sections of the book were the three that those two bookended. Clausius’ story was probably the least familiar to me, as I probably couldn’t have named him if asked. And what made his story interesting was how many other discoveries or developments had to happen along the way for him to be able to articulate his equation – including the invention of the thermometer, the creation of the calorie as both a unit and as a theory for the source of energy, and the life’s work of Julius Robert Mayer, a Bavarian doctor who first expostulated that all the energy in the universe had to add up to the energy that existed at the universe’s start (that is, the First Law of Thermodynamics), only to find himself rejected and ostracized by both the scientific and religious establishments of the time.

The final section of the book, on how Einstein’s theory of relativity led to the development of nuclear weapons, is a bit poignant as Einstein lived to see the destruction and regretted his role in encouraging President Roosevelt to order the development of the bomb. (I would imagine Einstein realized, however, that since the Germans would have eventually developed it themselves, the Manhattan Project was as much as a defensive move as an offensive one, even though it became an offensive weapon when we figured it out first.) Slightly less interesting, to me at least, was the extent of the family squabbles in the section on Bernoulli, where a pattern of fathers becoming jealous of talented sons tended to repeat itself in a way that would probably land them on Maury Povich today.

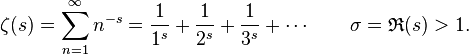

If you like the sound of this book but want something mathier, check out my review of Prime Obsession, a book about the development of the Riemann Hypothesis, perhaps the leading unsolved problem in mathematics today.